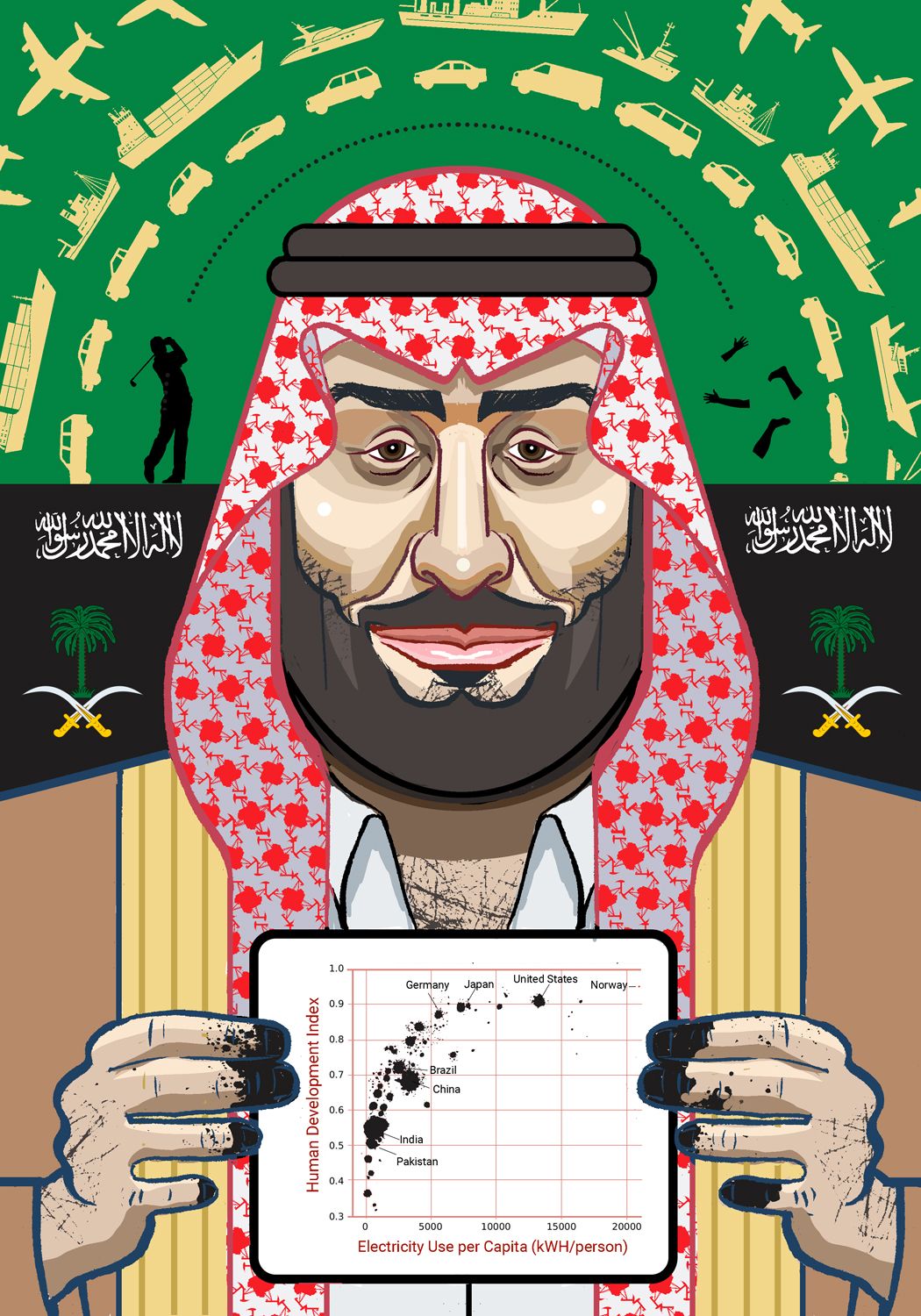

As a teenager, Mohammed bin Salman was obsessed by powerful men like Alexander the Great. No matter that he was so far down the line of succession that his elder half-brothers and cousins would guffaw at the prospect of him becoming king (or becoming anything), while sending him to the

As a teenager, Mohammed bin Salman was obsessed by powerful men like Alexander the Great. No matter that he was so far down the line of succession that his elder half-brothers and cousins would guffaw at the prospect of him becoming king (or becoming anything), while sending him to the shop to pick up cigarettes.

Later, as he forged alliances, amassed a huge fortune and outmaneuvered his rivals in the royal family, MBS, as he's known, reflected on the people who had "Great" attached to their names. They didn't get the moniker because of kindness or beneficence. These men were feared. They certainly didn't take orders from self-appointed global superpowers ... and they ruthlessly removed anyone who'd dare challenge their mandate. That was the era of Sun Kings and Emperors.

After the brutal murder of Jamal Khashoggi in 2018 by assassins working directly for Mohammed bin Salman, many thought the Saudi crown prince’s meteoric rise would stall and crash into the bottom of the sea. World leaders shunned him, and columnists saw the rest of his actions — his deep involvement in Yemen’s civil war, his jailing of activists, the Ritz “sheikhdown” — with blood-tinted spectacles. His work opening Saudi Arabia's economy and public society up to women was seen as hollow because of a crackdown on women activists.

This story is open to all and our work is available for free to anyone who signs up with their e-mail. But investigations like this aren't cheap. If you believe accountability journalism matters, consider upgrading to a paid subscription—or sending a one-time boost. Every contribution directly funds more reporting like this.

Have a tip? Reach us at:

📩 whalehunting@projectbrazen.com

📧 projectbrazen@protonmail.com

🔒 Secure contact details here.

We protect our sources.

Joe Biden’s team, in one of its first foreign policy moves, announced that the U.S. president would only meet with his counterpart, MBS's elderly father. MBS was toast, pundits said. Surely, the Saudi royal family would do the right thing and appoint a less mercurial, less ambitious successor...

Related Posts

Related Posts