A mysterious South African took over a sovereign nation, armed with a flood of untraceable wealth from scam compounds enslaving thousands. This is the story of how Chinese organized crime captured Thailand — and why America should be terrified.

Welcome to Whale Hunting, where we protect our sources and stand up to the powers that be in our effort to illuminate the hidden worlds of money and power.

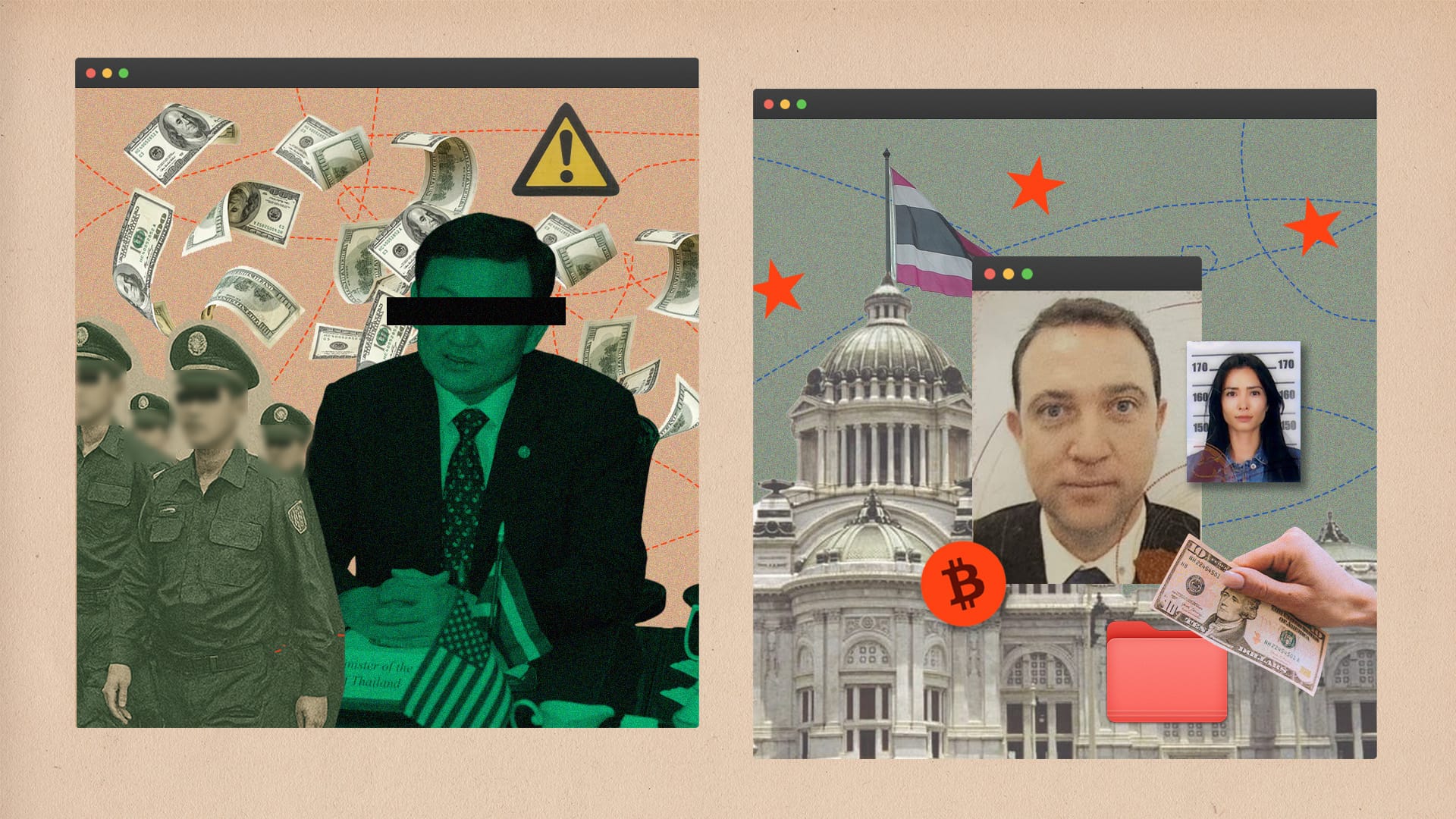

Our readers will know that we've engaged in an intense investigation into the story of fraud and money laundering that all started with the case of Benjamin Mauerberger. After months of investigation across six countries and interviews with more than fifty sources, we're publishing our most detailed account yet of how Mauerberger and the Chinese mafia infiltrated Thailand's government — representing the most complete case of state capture in modern history and a new threat to American security.

We are deeply grateful to our readers for sticking with us, even when it gets a little edgy. Please forward to anyone you think is interested with a request that they consider subscribing.

— Tom and Bradley

Enjoying this investigation? Get our exclusive reports delivered to your inbox.

Subscribe FreeGet the full story—free with your email.

This story is open to all and our work is available for free to anyone who signs up with their e-mail. But investigations like this aren’t cheap. If you believe accountability journalism matters, consider upgrading to a paid subscription – or sending a one-time boost. Every contribution directly funds more reporting like this.

Have a tip? Reach us at:

📩 whalehunting@projectbrazen.com

📧 projectbrazen@protonmail.com

🔒 Secure contact details here.

We protect our sources.

This summer, a mysterious South African called Benjamin Mauerberger waited outside a meeting of Thailand's cabinet. As the cabinet filed out, Mauerberger cornered Finance Minister Pichai Chunhavajira in a private room. Although a foreigner, Mauerberger had become a commanding figure in Thailand's government and he was enraged that Pichai had dared to block his policy. As the debate got heated, Mauerberger whispered to the minister, with an undercurrent of menace: "I outrank you."

At 47, Mauerberger is a towering, broad-shouldered presence who once could have been mistaken for a boy band member. But the years have exacted a toll: deep lines cut below his eyes, his hair is in retreat, and a constant, visible twitchiness betrays decades spent dodging global arrest. He moves with a powerful, coiled tension, juggling multiple burner phones as he dominates his Asian associates. When one businessman pressed him for a surname, Mauerberger offered a charmed but empty smile: "Just Ben."

Mauerberger is a central node in what U.S. officials call the Chinese mafia — a sprawling, decentralized network of criminal organizations that the United States Institute of Peace estimates generates $64 billion annually through cyber-enabled fraud. The Federal Trade Commission believes the true figure, accounting for unreported losses, may approach $200 billion — more than the annual revenues of Ford, Bank of America, or General Motors. The victims are ordinary Americans: retirees, small investors and lonely professionals who fall for fake crypto schemes and romance scams, often losing their life savings. Some have killed themselves.

The money flows to prison-like scam compounds across Southeast Asia, where trafficked workers spend 17-hour days calling cell phone numbers in the U.S., then gets laundered through banks, shell companies, and complicit politicians.

"The scam centers are creating a generational wealth transfer from Main Street America into the pockets of Chinese organized crime," U.S. Attorney Jeanine Pirro said in November.

Mauerberger's infiltration of Thailand's government — not just police and politicians, but the Prime Minister's inner circle, army generals, and financial regulators — represents the most complete case of state capture in modern history, and the clearest illustration of why this new enemy is far harder to fight than the American Mafia of the 20th century.

Starting last year, Mauerberger, who also goes by "Ben Smith," began to act as an unofficial Thai government minister. He bragged to friends in Bangkok that he controlled $4 billion in assets: a $20 million Aman penthouse opposite Trump Tower in New York; a $100 million super yacht called "Wanderlust"; a $80 million Airbus private jet. He showered gifts on Thai politicians — millions of dollars in crypto, luxury cars, financing for political parties — and secretly acquired a controlling stake in a Thai investment bank. One of his key initiatives was an official government blueprint for Thailand's digital economy, although his name appeared nowhere on the document. On the surface, it was an ambitious plan to make Thailand a leader in crypto. In reality, Mauerberger needed to secure rapid, high-volume conduits to move billions of dollars in illicit cash — and fast.

He was right to be paranoid. In 2023, a CIA agent in Bangkok began tracking Mauerberger's unexplained fortune. Following the money back to Cambodia — a neighboring state long ceded to China's influence — the agent came to understand that Mauerberger was not a mere money launderer but an important player in a criminal network the size and power of which the world has rarely seen. The agent wanted to build a formal case file, but his supervisor dismissed the lead. Mauerberger, the boss concluded, was not dangerous. When the agent rotated out of Bangkok, he didn't even leave files for his replacement. The trail went cold — for a time.

Fighting this Chinese mafia was going to be more complex than the 1990s takedown of the American Mafia. In the 1970s and 80s, John Gotti's ruthless economic capture peaked by buying off local police and politicians to control industries like construction and waste disposal. His organization, however, was a rigid pyramid: when Gotti's trusted lieutenant, Salvatore "Sammy the Bull" Gravano, flipped, the entire centralized structure collapsed. That was the playbook — flip one guy, get the whole pyramid. But the new enemy is structurally different. Fueled by billions in crypto, these networks — actually hundreds of loosely interconnected groups, and their intersection with crypto money launderers like Mauerberger — have subverted not just local cops, but entire sovereign governments: Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar. The Italian Mafia was a single octopus with a central brain and many arms. This is a school of octopuses swimming in the same direction — sometimes coordinating, sometimes independent, but impossible to decapitate.

Americans don't even see the threat coming. We learned to fear the Mafia through a century of myth-making — The Godfather, Goodfellas, The Sopranos. We know the don, the consigliere, the code of omertà. But there is no Chinese Corleone, no triad saga that crossed over into the American imagination. Hong Kong made great gangster films; Hollywood remade the best of them, Infernal Affairs, as The Departed — and erased the Chinese entirely. The threat is invisible not just because it's decentralized, but because we have no story for it.

This account of Mauerberger's rise — and the criminal network he served — is based on interviews with more than fifty people across Thailand, Cambodia, Singapore, Dubai, the United Kingdom, and the United States, including former associates, law enforcement officials, and victims. It draws on hundreds of corporate records, financial documents, internal communications, and photographs. Mauerberger, through a statement, has denied any wrongdoing and called this reporting a "relentless smear campaign." He denied any connection to Cambodian money laundering, call-center scams, or human trafficking. "I have never had and will never have any connection to such activities," he said.

Become a subscriber to read the full story and support independent journalism.

Subscribe NowOne evening in October, an American executive logged on to Feeld, a dating app for the kink community. He believed he was texting with a beautiful woman, and they shared explicit photos. Moments later, his phone rang, and a man with a hard-to-place accent calmly informed the executive that this was a shakedown. "You're a businessman. This is just business," the voice said. The approach was so flawless it had entrapped a sophisticated person. These were not amateurs.

After the man on the phone threatened to send the compromising photos to business associates, the executive agreed to pay: $5,000, $10,000, and then $15,000. The demands kept escalating. Finally, the executive cut contact. Satisfied with the haul, the caller moved on to the next victim.

Sextortion is one of the fastest-growing crimes in America. While such blackmail is fast-paced, scammers often spend months building a relationship with a victim before convincing them to invest large amounts in fake crypto or foreign-exchange trading apps. The scam is known in Chinese as "pig butchering," because victims are fattened like pigs before losing their life savings. The psychological damage — shame, anger, hopelessness — is ruining countless lives. Several victims have killed themselves; at least 20 suicides between October 2021 and March 2023 were linked to sextortion incidents involving minors, according to the FBI.

On November 6, 2024, fifteen-year-old Bryce Tate of Cross Lanes, West Virginia — an honor roll student and basketball player — received his first threatening message from scammers posing as a local teenage girl. They knew which gym he worked out at, his friends' names, his basketball team. After getting compromising photos, they demanded $500. Bryce had $30 and begged them to take it. They refused and told him to kill himself "because your life is already over." In the last 20 minutes of his life, they sent him 120 messages. Within three hours of the first threat, he shot himself. "They say it's suicide, but in my book it is 100% murder," his father Adam told the New York Post. "They're godless demons."

In one extreme case of "pig butchering," a Kansas banker named Shan Hanes — a pillar of his community who had served on the board of the American Bankers Association and once chatted with Janet Yellen in a crowded elevator — embezzled $47 million from his small agricultural bank after falling for a crypto scam on WhatsApp. When a wealthy customer came to the bank one morning, Hanes pulled out his phone and showed him a screen displaying $40 million in supposed crypto holdings. "Brian, I need to borrow $12 million for ten days," Hanes said, "and I'll give you $1 million for loaning it to me." The customer thought he'd walked into a loan shark's office, not a bank in rural Kansas. Hanes' embezzlement caused the bank's collapse and earned him a 24-year prison sentence — the longest ever in Kansas for a white-collar crime. The scammers who manipulated him have never been identified.

The U.S. is fighting to protect its citizens. In October, the Justice Department unsealed an indictment against Chen Zhi, a baby-faced 37-year-old Chinese émigré who had risen to the highest echelons of power in Cambodia, a Southeast Asian state known in the U.S., if at all, for the Khmer Rouge genocide in the 1970s. A Thai actor who met Chen in 2018 recalled the encounter years later: "He was very much — I don't want to make this too dramatic — but very much like a godfather. He didn't say much, I believe, except hello. He seemed so powerful."

Chen held British and Cambodian citizenship and had become a naturalized Cambodian in 2014, a status available to anyone who donates $250,000 to the state. Few made the inroads he did. By 2017 he was an adviser to Cambodia's Interior Ministry; by 2020, a personal adviser to then-Prime Minister Hun Sen. He accompanied Hun Sen on diplomatic missions, including a trip to Cuba where he met President Díaz-Canel. He went into business with Sar Sokha, whose father was Interior Minister at the time; Sokha now holds the position himself. Their joint venture, Jin Bei Casino, is what the Treasury Department calls "among the most notorious" of Cambodia's scam compounds. When Hun Sen's son Hun Manet became Prime Minister, Chen was named among his 104 advisers — a rank equivalent to minister. In April 2023, according to the indictment, Chen entered the United States on a diplomatic passport, allegedly obtained after purchasing luxury watches worth millions for a senior Cambodian official.

Behind this façade, U.S. prosecutors allege, Chen ran one of the largest transnational criminal organizations in Asia. By 2018, his Prince Group was earning more than $30 million per day from crypto fraud schemes. The operation ran at least ten forced-labor compounds across Cambodia. Investigators found ledgers tracking profits by room, "phone farms" with thousands of devices controlling millions of accounts, and photographs of beatings and torture. The DOJ filed a civil forfeiture complaint for approximately 127,271 Bitcoin — worth roughly $15 billion — the largest asset seizure in the department's history. Chen remains at large.

The Chen indictment revealed an enormous criminal enterprise. But it also made clear how much remains hidden. The Brookings Institution has identified over 100 China-linked criminal networks operating in the region; researchers at Cyber Scam Monitor have documented more than 200 scam centers in Cambodia alone. Prince Group, for all its scale, was just one node among many.

Chen was the polished version of this world — officially embedded, bestowed with titles, photographed alongside heads of state. He drew attention to himself, not just from the American case, but from Chinese authorities. Benjamin Mauerberger operated differently. He offered his Chinese partners anonymity – the ability to remain one step removed from the movement of cash.

Mauerberger held no official titles in Thailand, but he wielded real power — confronting cabinet ministers, dictating policy, embedding his people in the regulatory infrastructure. There were almost no photos of him on the internet. Then, he got sloppy. He allowed a partner – wearing a $2 million watch – to post photos from a Gulfstream private jet . He bought assets under names that could be traced. He made enemies who talked.

He'd worked hard to stay dark. But Mauerberger, through his own mistakes, turned on the lights.

In 2018, Deng Pibing walked into the BIC Bank offices in Phnom Penh, Cambodia's capital, accompanied by Benjamin Mauerberger and a number of local VIPs. Now aged 45, Deng is short and composed, with a spiky head of black hair and round glasses.

Dressed smartly in a buttoned-up suit and pink tie, his hands clasped in front of him, Deng watched as the Cambodian VIPs were introduced. Behind him, Mauerberger, more casually dressed, with an open-necked shirt and suit jacket, smiled and chatted — taking a more backseat role.

The event marked the opening of BIC Bank, a new commercial lender that Mauerberger, Deng Pibing and their partners hoped would benefit from an unprecedented wave of Chinese investment into Cambodia. Chinese President Xi Jinping had encouraged huge state spending in Cambodia — largely directed at real estate, infrastructure, and casino development — to solidify Cambodia as a key ally, a geopolitical counterweight to U.S. influence. Around $1 billion in Chinese capital had poured into just one city, Sihanoukville, over the preceding 12 months.

Both Deng and Mauerberger sought new lives in this booming environment. Unusually for a Chinese businessman in Cambodia, Deng was a graduate of the Hunan University of Science and Technology and had worked a decade in IT in the country. He'd recently been granted Cambodian citizenship, but he maintained good relations with China's Communist Party. His new company, Zhengheng Group, was among the developers of Dara Sakor, an ambitious Chinese government-endorsed tourism and commerce project sprawling over 139 square miles — a fifth of Cambodia's total coastline.

Mauerberger's route to Cambodia was by necessity. He'd grown up in Cape Town, part of a formerly wealthy family that had owned textile and clothing businesses. By the 1990s, the family had fallen on hard times. His father had passed away young, and Mauerberger lived with his mum and siblings in a grungy beach area of the city. There was enough money for him to board at the posh Bishops Diocesan College. School mates remember him as a scrawny kid who was bullied, but later started to smoke and party. He left the school before graduating amid a cheating scandal – a group of kids bribed a man who worked in the printing room to give them copies of exams – and later completed his studies at another college.

After a short stint working in London in finance, Mauerberger ended up in Bangkok in the early 2000s. The Thai capital, known for its nightlife, had become a global hub for scamsters. Like Ben Affleck's character in the 2000 movie "Boiler Room," Mauerberger began selling fraudulent stock offerings to mom-and-pop investors around the world. A former associate says Mauerberger had matured into a good-looking guy and was a smooth talker, adept at persuading grandmas to buy worthless stocks.

He was also very skilled at not getting caught. While many of his associates ended up in jail, Mauerberger avoided prison, despite being sought at various times by authorities in Spain, the U.K., U.S., Australia, and New Zealand. But he couldn't risk traveling to many Western nations — he is on an intelligence watchlist in the U.K. — and constantly changed passports: the Central African Republic, South Africa, France, St. Kitts and Nevis.

Mauerberger was fairly well-off — he lived at the luxury St. Regis apartments in Bangkok with his second wife, a British-Thai former model called Cattaliya Beevor. The kids were in an expensive international school. But he was a striver, say people who knew him. He would try to make contact with rich socialites in the St. Regis, always overstating his connections to Thai elites. Most people had heard whispers of his boiler room profession, or knew him as a money launderer, but Bangkok was full of such Westerners.

After years of moderate wealth, Mauerberger itched to enter the big leagues. He was ashamed to still fly commercial, so would charter private planes and not pay the bill, says a person aware of the matter. When he ran out of money, Mauerberger — always charming — persuaded businessman Anutin Charnvirakul, who is now Thailand's prime minister, to lend him his Embraer private jet. He told those he gave lifts on the aircraft — mainly Asian business people — that the plane was his.

He became close to a Thai senator, but a deal they did together involving a power company led to heavy losses for many elite Thais. At one point, he flew up to northern Thailand to acquire cannabis farms — but the deal went nowhere. He tried and failed to broker a deal to sell Israeli guns and ammunition to Thailand's military. When the senator faced his own legal troubles for money laundering, Mauerberger told associates he didn't feel secure in Thailand. It was at this point he rode the wave of Chinese investment in neighboring Cambodia.

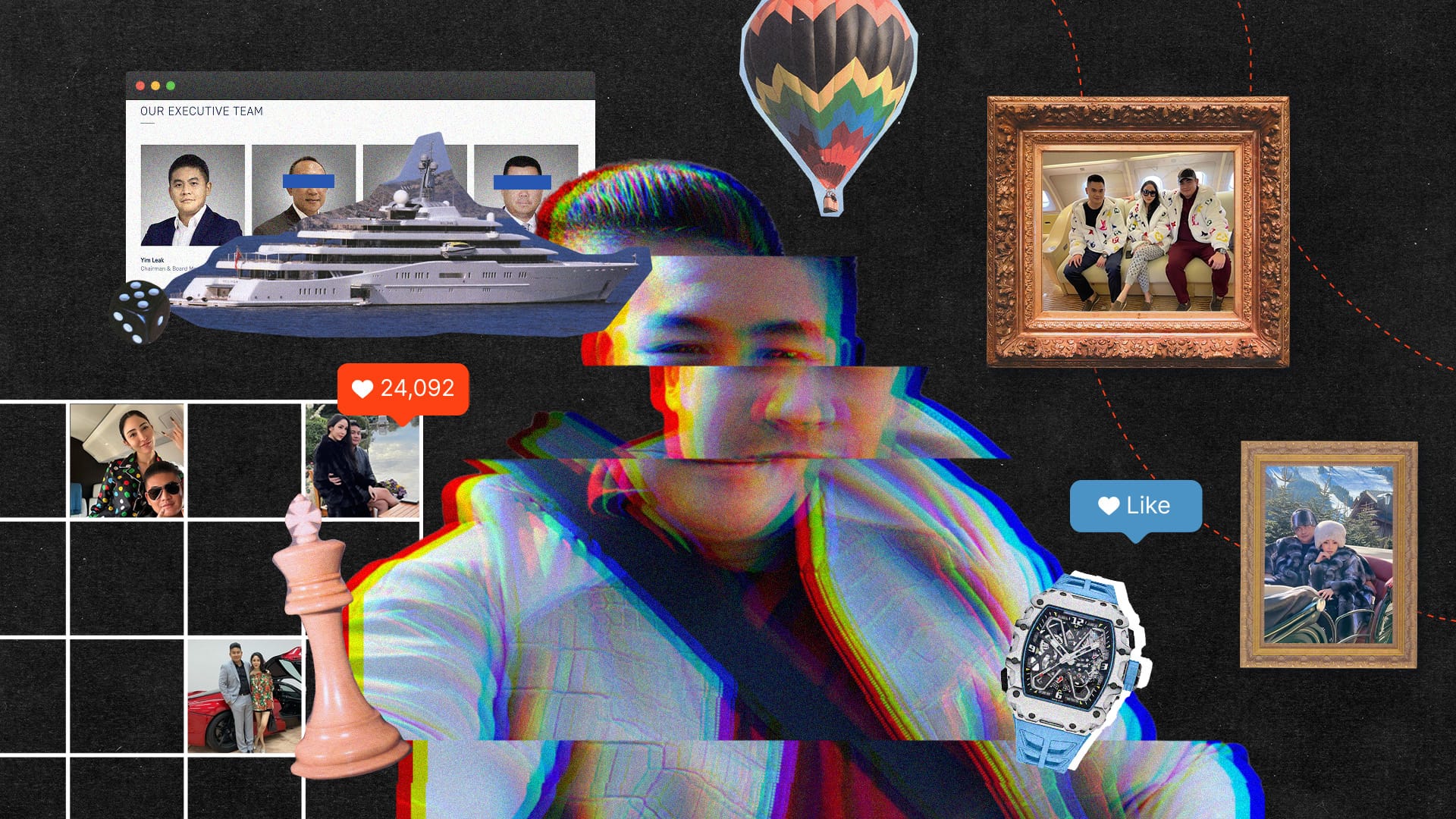

Mauerberger's entry into Cambodian high society came via a partnership with Yim Leak, a babyfaced playboy with slicked-back hair, eight years his junior. The pair had met after Mauerberger acquired a Cambodian passport and looked for opportunities in the country. Leak's family is political royalty: his father was a deputy prime minister and his sister is married to Hun Sen's son. In the closed world of Cambodia's elite, the pair got to know Deng Pibing, the Chinese businessman, and in 2018, they combined forces to set up BIC Bank to tap into Chinese investment in Cambodia.

Leak spent all day playing computer games in the office and liked sports cars and partying, while Mauerberger, an abstemious drinker, was the true power inside the bank. Leak was also a director of Queenco Casino in Sihanoukville, according to Cambodia's corporate registers, and would watch his dealers via a live camera link on his phone — unable to stop monitoring his money.

At first, Mauerberger boasted to friends that BIC Bank was thriving. Chinese President Xi Jinping's "sweep black" anti-corruption campaigns had driven thousands of gangsters offshore, and Cambodia — with its compliant politicians and porous borders — became their preferred destination. BIC Bank washed money for Chinese-controlled casinos and opened trusts so Chinese investors could buy land in Deng Pibing's huge tourism and commerce development.

But soon after its launch, BIC Bank was in trouble. Beijing had grown especially perturbed about the growth of online casinos, which Chinese gangs were using to illegally sidestep China's strict capital controls. Under Chinese pressure, Cambodia shut down the sector. Overnight, hundreds of thousands of Chinese left the country. Those involved in huge infrastructure projects like Deng Pibing — and by extension Mauerberger — were in trouble.

Faced with empty casinos, hotels and resorts, the Chinese gangs that had been involved in online gambling pivoted. Collaborating with existing human trafficking networks, these groups converted the empty complexes into heavily guarded, clandestine scam compounds — the slave trade of the 21st century.

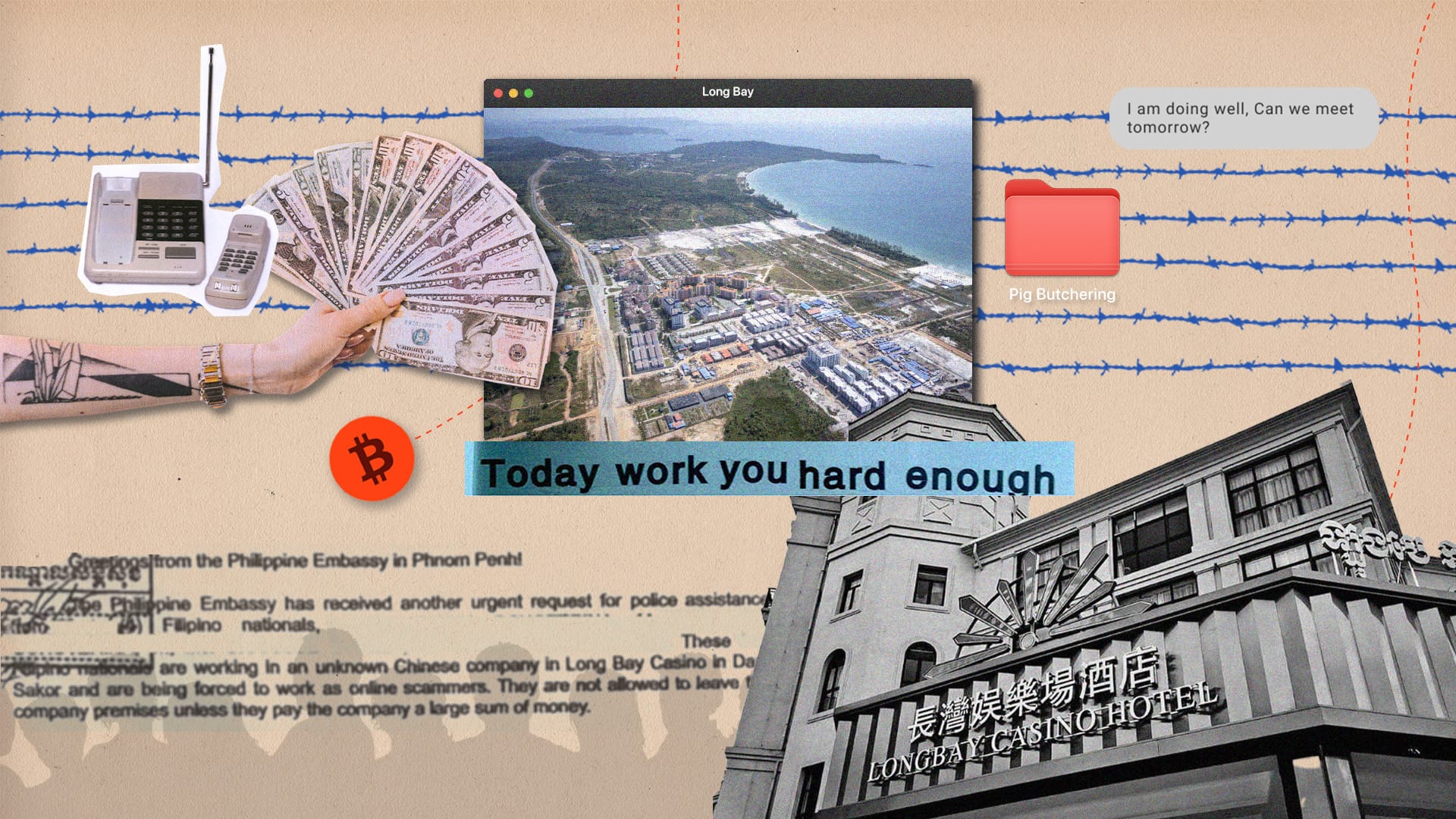

Kris, a 31-year-old customer service rep from the Philippines, realized something was very wrong as the van hurtled past the outskirts of Phnom Penh and into Cambodia's jungled interior. The nerve-wracking six-hour journey ended at Long Bay resort where he discovered the job he'd applied for on a Facebook forum wasn't what it seemed. Instead of helping clients with a new software package, Kris was forced to chat up Westerners on social media and slowly lure them into investing in rigged — or wholly fabricated — cryptocurrencies.

The U.S. State Department estimates between 100,000 and 150,000 workers — Taiwanese, Filipinos, Indians, Indonesians, Africans, even Ukrainians — remain trapped in similar conditions across Cambodia. Lured with the promise of white-collar jobs at casinos paying $1,000 or more per month, these workers become slaves, their passports impounded until they have "worked off" fictitious debts, as Kris eventually did. Beatings, torture, and sexual violence are commonly reported.

The developer of the Long Bay resort – part of the Dara Sakor development – was Deng Pibing's company, Zhengheng. In 2018, Deng had entered a business partnership with She Zhijiang, a Chinese gambling kingpin who would later be sanctioned by the U.S. Treasury for building a $15 billion scam fortress on the Myanmar-Thailand border. Corporate records show they jointly owned a Hong Kong company called Cosmos Rise, and appeared together at Long Bay's groundbreaking ceremony, pouring ceremonial sand. Deng later claimed he cut ties with She upon discovering his "unreliability" — but the partnership showed how interconnected Cambodia's criminal economy had become.

With a luxury casino and hotel at its center and a beach nearby, the Long Bay resort was supposed to be the crown jewel of the larger Dara Sakor development. But after Cambodia's ban on online gambling, followed by a slump in tourism due to Covid-19, the Long Bay project became a ghost town of half-completed buildings with only a fraction of the intended 80,000 population.

Instead of tourists, criminal gangs moved in, overseeing perhaps 2,000 workers who spend 17-hour days making calls to cell phone numbers in the U.S., Europe and Asia, trying to lure victims to invest in fake cryptocurrencies, or send compromising sexual photos. The money that Kris and workers like him helped steal — taken from Americans who would never know his name — would flow through BIC Bank within days, transformed from stolen crypto into clean cash.

Soon, Deng was depositing huge amounts of cash in BIC Bank — in which he held a minority stake — sometimes as much as $60 million a day, says a person aware of the business. Deng was the bank's largest customer, but not the only one; BIC Bank served as a laundromat for many Chinese businesses operating in Cambodia's grey economy. At one point, the bank was listed on Zhengheng's website as a "diversified business" — a relationship that would later lead the U.K. Treasury to call it a Zhengheng "subsidiary."

The mechanics of the money laundering were straightforward. Scam compounds like Long Bay would steal cryptocurrency from victims. Intermediaries like Cambodia's Huione Group converted the crypto to dollars — for a steep fee. The cash was then deposited at BIC Bank and wired to Kasikorn Bank in Thailand, citing a crypto mining operation that Mauerberger controlled in Laos as a plausible source of funds. To ensure the central bank never asked questions, Yim Leak paid Cambodian officials roughly $100,000 a month, says a person aware of the arrangement. In 2022, Cambodia's central bank flagged $84 million in suspicious transactions — but the money went through anyway.

Mauerberger told associates that he and Leak took a 20% cut of all transactions — a laundering fee. But the person aware of the business said Mauerberger and Leak often just stole deposits outright. The Chinese businessmen who deposited money were engaged in criminal activities themselves; they were in no position to complain. It was the price of doing business.

By 2021, Mauerberger no longer needed to borrow private jets; he bought his own — a Gulfstream G550 worth tens of millions of dollars — raising questions in his circles about how he could afford such a luxury. He developed an authoritarian streak, demanding subordinates complete tasks within minutes. He was jokingly referred to as "Hitler," a bad-taste nickname given his Jewish heritage, but one he didn't mind.

Mauerberger started to fly from Phnom Penh – where he stayed in the luxury Rosewood Hotel – to Bangkok in the Gulfstream with suitcases full of cash, some of them locked tight with chains. The South African would often ask for the plane to be ready at 5:30 am but wouldn't turn up until 11 am, say people who traveled with him. Plans changed abruptly. Once he arrived, Mauerberger boarded quickly, often with his wife, Cattaliya, and would ask not to be disturbed in the cabin. The flight attendants — beautiful Thai women who made Cattaliya jealous — weren't happy. It was clear something shady was afoot.

The Achilles heel was Yim Leak. For years, Mauerberger had maintained a low profile. It took some digging to find photos of him: there was one from a Bangkok nightclub in 2012, another with some businessmen in Vietnam, another with him playfully holding one of Yim Leak's combat assault rifles. But almost nothing recent. Leak and his wife, on the other hand, couldn't help but show off on Instagram. Leak posted a photo from the Gulfstream, wearing a $2 million Richard Mille Tourbillon Skull watch, his wife in Louis Vuitton pajamas. He was photographed in Bangkok driving a $3.5 million Bugatti Chiron with a "Boss" numberplate.

This was unwanted attention.

In 2021, horrifying videos and photographs of atrocities inside scam compounds began to surface on the internet — people being struck with electric batons, chained to iron bed frames. This drew Cambodian and international media attention. The Voice of Democracy, a Cambodian news agency, wrote an exposé of the slave-like conditions at Long Bay's scam centers, citing a Taiwanese victim who managed to get out after paying a ransom. Deng Pibing denied any knowledge. He said Zhengheng owned the land and developed Long Bay, but had no control over the activities inside.

As the media reports piled up, the FBI began to connect the dots between the forced labor in Cambodia and money lost by Americans. Agents from the FBI's New York Joint Asian Criminal Enterprise Task Force would eventually focus on Chen Zhi and his Prince Group — the network that led to the $15 billion asset seizure. But Chen, for all his scale, had hidden his illicit business behind a facade of legitimate-looking property, finance and other companies; it took years for Western law enforcement to build a case.

Beijing, too, began to crack down. She Zhijiang, Deng Pibing's former partner, was extradited to China in November 2025; Beijing accused him of operating over 200 illegal gambling platforms targeting Chinese citizens. But Deng seemed protected by his Communist Party ties. Deng regularly traveled back to Hunan, where he donated $3 million to his alma mater. High-ranking Communist Party members attended the ceremony, which was covered by state media. Unlike Chen, who also drew Beijing's scrutiny for targeting Chinese victims, Deng was more careful. And unlike Chen, who built visible infrastructure like Prince Bank, Deng could rely on Mauerberger to launder the money coming out of Long Bay without boosting his visibility.

"This is a guy who has covered all his bases," says Jason Tower, a senior expert at the Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime. "He's a more savvy operator."

As long as Deng only targeted Americans, and didn't embarrass China, his position seemed secure. Criminal syndicates had learned the lesson: Beijing cracked down ferociously when Chinese citizens were victimized, but crimes against foreigners barely registered. "As long as we didn't scam Chinese people and only scammed foreigners, no one would care," one convicted scammer told Chinese police. But then, in December 2023, the U.K. Treasury sanctioned Zhengheng for human rights abuses, claiming individuals were held at Long Bay against their will and "forced to work as scammers." The official sanction notice listed BIC Bank as a subsidiary of Zhengheng, although it did not mention Deng, Mauerberger, or Yim Leak.

With this heightened scrutiny, Mauerberger's network was going to need some top-level political cover. Help came in the form of the patriarch of Thailand's most powerful political family.

Soon after Thaksin Shinawatra returned to Thailand after 15 years in exile, he tapped out a message on WhatsApp, requesting an associate meet Benjamin Mauerberger. The South African was an important ally, Thaksin said. Now 76, Thaksin was a former Prime Minister of Thailand and a billionaire businessman — a populist, widely loved in rural areas — but had been forced into exile years earlier amid corruption allegations. In that time, he'd bought and sold UK soccer club Manchester City, invested in gold mines in Africa, and built a Thai property empire through family proxies.

While in Dubai, where he'd spent most of his exile, Thaksin had gotten to know Mauerberger. The South African was now a major player. With Yim Leak, he hosted Chinese, Thai, and Cambodian VIPs on their super yacht. He collected real estate around the world — New York, Dubai, Bangkok — and drove an orange-colored McLaren. Yim Leak bought a Versace-designed penthouse in London.

Over his years in Bangkok, Mauerberger had built high-society connections: the chief of the country's armed forces, a senior police general, the CEO of a Thai bank, and a Thai senator. But his business deals had never really flourished. Now he had the financial muscle to make a difference at the highest level. After Thaksin returned from exile, Mauerberger boasted to numerous people that he was making political donations to help the Shinawatra family come back to power — paying off political parties that would eventually bring Thaksin's daughter to the premiership. He bragged often that he was meeting with "Dr. T." One associate says Mauerberger showed him a crypto account containing hundreds of millions of dollars that he claimed belonged to Thaksin. When Paetongtarn Shinawatra became Prime Minister in August 2024 — with her father pulling the strings — Mauerberger was in a powerful position. A lawyer for Thaksin has said he knew Mauerberger only as an "acquaintance."

The old ways of moving money — chained suitcases on the Gulfstream, transfers from BIC Bank — were inadequate as hundreds of millions of dollars in scam proceeds poured out of Cambodia. Mauerberger needed an industrial channel to wash cash. In Singapore, a respected regional financial center, he set up a fund management company called Capital Asia Investments, nominally run by two Singaporean wealth managers, but Mauerberger made the decisions, say people familiar with the matter.

Starting in mid-2024, using nominees and complicated fund structures in Singapore, Mauerberger illegally acquired a controlling stake of Finansia, a Thai investment bank and securities firm, documents show. Thai SEC rules don't allow "concealed control" of a financial institution. Until then, BIC Bank had moved money via Kasikorn, an unrelated Thai bank — now Mauerberger controlled his own institution.

But this was just phase one of his plan. In Cambodia, intermediaries like Huione Group took billions of dollars in crypto from scams and converted it to cash. As Huione came under U.S. regulatory scrutiny, eventually getting cut off from the U.S. financial system and closed down in Cambodia, Mauerberger worried about creating a new on-off ramp.

To do so, he partnered with KuCoin, a disgraced global crypto exchange, to whose Chinese owners Thaksin had made introductions back in Dubai. In January, KuCoin pleaded guilty in the U.S. to money laundering and agreed to pay $300 million in fines to the Justice Department for allowing $9 billion in criminal transactions on its exchange. As KuCoin was pleading guilty, however, the company's local representative, Henry Chen, was scheming with Mauerberger.

In late 2024, Mauerberger secretly negotiated an MOU with Thailand's Ministry of Digital Economy and Society to develop the country's crypto sector. The cornerstone of the plan — pushed in public speeches by Thaksin — was a baht stablecoin, an official way to convert cryptocurrency into Thai baht. Mauerberger was accruing incredible powers. The MOU gave him direct control over Thailand's digital sector, and he brought in KuCoin's Henry Chen, a Chinese national who had worked for Goldman Sachs, to advise on the stablecoin and other policies.

At the same time, fronts for KuCoin illegally took stakes in Finansia, secretly integrating a crypto exchange with the banking sector – a channel to move stolen crypto into the banking system without oversight. The MOU also allowed Mauerberger to deploy 500 "IT specialists" in Thailand — giving visas to embed his network deep into Thailand's digital and regulatory infrastructure.

Through lawyers, Chen has denied any knowledge of unlawful activities and says he had no contact with Thai political figures, political parties, or regulators. He has called the reporting against him "false and groundless" and threatened legal action.

Almost all digital business in Thailand touched Mauerberger: When Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI, rolled out his controversial iris-scanning digital identity technology in Thailand, a company controlled by the South African was the local partner; Thaksin promoted the business by appearing on stage with Altman's co-founder.

Thaksin began to rely on Mauerberger for other matters, including a contentious proposal to legalize gambling in Thailand. When William J. Hornbuckle, the CEO of MGM Resorts International, attended a meeting in Bangkok to discuss a new casino, his entourage was surprised that Mauerberger was present, says a person aware of the gathering. MGM had announced publicly that Hornbuckle and MGM China's Pansy Ho would visit Thailand in August 2024 to explore the opportunity — what they hadn't expected was to find a mysterious South African in the room, apparently calling the shots.

Fronts for Mauerberger also began to buy up stakes in Bangchak, Thailand’s second-largest energy company. The plan, says a person aware of the matter, was for Bangchak to benefit from an agreement between Thaksin and Hun Sen to open up development of oil-and-gas reserves in contested waters in the Gulf of Thailand. It was a dispute over this plan that led Mauerberger to publicly pull rank on Finance Minister Pichai, a former chairman of Bangchak, outside the meeting of Thailand’s cabinet.

In Cambodia, Mauerberger's influence also was growing. In 2024, Hun Sen appointed him and Yim Leak as official advisers.

This was the apex of his power — dictating Thai policy, embedded in Cambodia, and partner to powerful Chinese — emboldened by money stolen from Americans. Mauerberger, however, had flown too close to the sun.

In 2023, Benjamin Mauerberger came to our notice after he bought the Gulfstream private jet. Just as Jho Low — the Malaysian businessman at the center of the 1MDB scandal — had drawn attention to himself with purchases of super yachts and planes, so too did Mauerberger. But it was Yim Leak's flashy "Ibossleak" Instagram account that really put the pair out in the open.

We reported on how Leak was posting from the Gulfstream, bought for him by Mauerberger. Why was a South African traveling on a Cambodian diplomatic passport under the name "Ben Smith"? An internet search showed his boiler room history and legal troubles in New Zealand, Australia, Spain, U.S., and the U.K.

Soon after we published our story, Leak deleted his Instagram account. We moved on, but Mauerberger kept acquiring assets. Earlier this year he bought a $60 million Bombardier Global G7500 private jet, which Thaksin Shinawatra began using. He even lent his "Wanderlust" yacht to Thaksin in December 2024 for an important diplomatic meeting with Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim.

These kinds of purchases, especially without a clear source of funds, put Mauerberger on the map. But he'd also made enemies. In Bangkok, there are many people who claim to have lost money in deals that Mauerberger led. There are many who feel cheated. And there are others who believed Mauerberger held too much power, especially for a foreigner. Among them was Sarath Ratanavadi, the billionaire founder of Gulf Energy and close Thaksin ally, who became angered with Mauerberger's growing influence — especially his push to control rival energy company Bangchak.

Mauerberger might have held onto his power but for one disastrous event. On May 28, tensions flared along the Thai-Cambodian border when an armed confrontation killed a Cambodian soldier. To deescalate, Prime Minister Paetongtarn Shinawatra called former Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen — a longtime friend of her father's whom she addressed as "uncle." In the 17-minute conversation on June 15, she urged Hun Sen not to listen to "the opposite side" in Thailand, including an outspoken Thai army commander she said "just wants to look cool." She added: "If you want anything, you can just tell me, and I will take care of it." What she didn't know was that Hun Sen's phone was recording.

On June 18, Hun Sen shared the audio clip with 80 officials on a WhatsApp group. The subsequent leak to Thai media caused a political firestorm. Opponents accused Paetongtarn of compromising Thailand's national interests. The Constitutional Court suspended her on July 1. And as Thailand's political crisis deepened, the border dispute spiraled into open warfare — artillery exchanges, rocket fire, villages evacuated. By the time a ceasefire was brokered, at least 38 people were dead and hundreds of thousands displaced. On August 29, the court removed Paetongtarn from office, the third Shinawatra to be ousted from the premiership.

No one knows for sure who leaked the call. Perhaps Hun Sen had expected to make money from deals in Thailand involving Mauerberger but, like many others, had been shortchanged. Maybe he was angered by Thailand's move to encroach on casinos, the lifeblood of Cambodia's dark-money economy.

Or could someone irked by Mauerberger's meteoric rise under Thaksin — and his entanglement with Cambodia — have been involved? It seems possible.

After we published a photo of Thaksin and Mauerberger meeting in Gaysorn Plaza in Bangkok, Thai media began to ask questions about the third person in the photo, whose face was obscured. It was Deputy Prime Minister Thammanat Prompao, a man who spent time in jail in Australia for heroin trafficking. Once identified, Thammanat jumped to Mauerberger's defense. He threatened to issue an Interpol Red Notice for our arrest.

Mauerberger's protective layer began to unravel. After we wrote that Deputy Finance Minister Vorapak Tanyawong's wife had been paid a $3 million crypto bribe in connection with Mauerberger's illegal takeover of Finansia, the investment bank and securities firm, Vorapak resigned. He denies wrongdoing and has threatened legal action.

By then, the U.S. had begun a probe into Mauerberger. U.S. Homeland Security Investigations picked up the trail that the CIA agent in Bangkok had abandoned years earlier — and this time, the investigation had traction.

On Dec. 2, the Royal Thai Police made 29 arrests in connection to a "transnational criminal network" centered on Benjamin Mauerberger and Yim Leak. "Both men's connections to influential figures in Cambodia allowed them to avoid scrutiny," the police said in a statement.

Another 13 people, including Yim Leak and his Thai wife, remained at large. Weeks earlier, the couple had emptied their Bangkok apartment and fled by private jet to Cambodia, where they are untouchable. BIC Bank was wiped from Cambodia's corporate registry, as if it had never existed. As for Deng Pibing, he hasn't commented, and is believed to be in Cambodia. His company's website has been taken down.

Thailand's police fanned out across the country, seizing almost $300 million in assets connected to Mauerberger and Leak, including a yacht, luxury cars, and Thai equities. The police statement, perhaps not surprisingly, made no mention of the high-level protection Thailand's elite gave to Mauerberger for years. While there is, as yet, no formal arrest warrant for Mauerberger, Thai authorities continue to build a case against him.

In late October, Mauerberger and his wife emptied their Bangkok apartment, took the kids out of school, and fled to Dubai, where they are currently believed to be living. He's reportedly trying to secure a new passport.

Justice is never perfect. Ten years after he was charged, the mastermind of the 1MDB heist, Jho Low, remains shielded in China by state protection. BIC Bank has vanished from Cambodia's records. Kris, the Filipino worker who once spent 17-hour days stealing crypto at Long Bay, has found his way home — one of the lucky ones. And somewhere in Dubai, Benjamin Mauerberger is making calls on his burner phones, still controlling enough money to matter, still knowing enough about elite corruption to be dangerous.

— Jacob Sims and Coby Hobbs contributed to this story.

This investigation builds on months of reporting. Read the full series:

Check out the Brazen Whale Hunting Collection.

Support accountability journalism

Investigations like this take months of work. Help us continue.

Subscribe Shop MerchGot a question or a tip for us? Get in touch at whalehunting@projectbrazen.com. You can also contact us securely here.

You can also follow Whale Hunting on Instagram, Threads and on X (Twitter). To chat with fellow Whale Hunters and stay in touch with Bradley and Tom, join our Discord server.

For unlimited access to Whale Hunting’s investigative reporting, consider signing up for a paid subscription. You’ll get special editions of the newsletter and the Weekender, as well as premium podcast access and discounted merch.

Enjoying Whale Hunting but not ready to subscribe? Show your support by leaving a tip (via credit/debit card or crypto) instead.

Related Posts

Related Posts