It’s not often that China’s biggest bank finds itself victim of a cyberattack so ferocious that it has to abandon its corporate email in favour of Gmail.

Welcome to Whale Hunting, a weekly newsletter delving into the hidden worlds of wealth and power from the team at Project Brazen. Catch up on all Project Brazen's work here, including Spy Valley (Tribeca Film Festival "Official Selection 2023"). Our new show The Professor, a thrilling art crime investigation, drops on Monday.

It’s not often that China’s biggest bank finds itself victim of a cyberattack so ferocious that it has to abandon its corporate email in favour of Gmail. But over the course of one afternoon earlier this month, employees at the New York office of the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) found themselves locked out of their accounts and watching helplessly as the company’s data was ransacked, encrypted, and held hostage.

Within hours, a backlog of unprocessed U.S. Treasury trades led to the bank briefly racking up $9 billion in debt to Wall Street neighbour BNY Mellon. In an effort to settle trades, ICBC offered to manually put its payment information onto a USB stick and send it by messenger across Manhattan. (BNY, it seems, politely declined this option, and managed to provide an alternative method).

This story is open to all and our work is available for free to anyone who signs up with their e-mail. But investigations like this aren't cheap. If you believe accountability journalism matters, consider upgrading to a paid subscription—or sending a one-time boost. Every contribution directly funds more reporting like this.

Have a tip? Reach us at:

📩 whalehunting@projectbrazen.com

📧 projectbrazen@protonmail.com

🔒 Secure contact details here.

We protect our sources.

So who was behind the attack? None other than the same prolific hacker group that published 50 gigabytes of internal data robbed from Boeing back in January. Boeing decided against paying a ransom, but ICBC decided its data was too important to lose. LockBit, the group that took responsibility for the attack, confirmed to Bloomberg that ICBC had paid them an undisclosed amount to get its files unlocked.

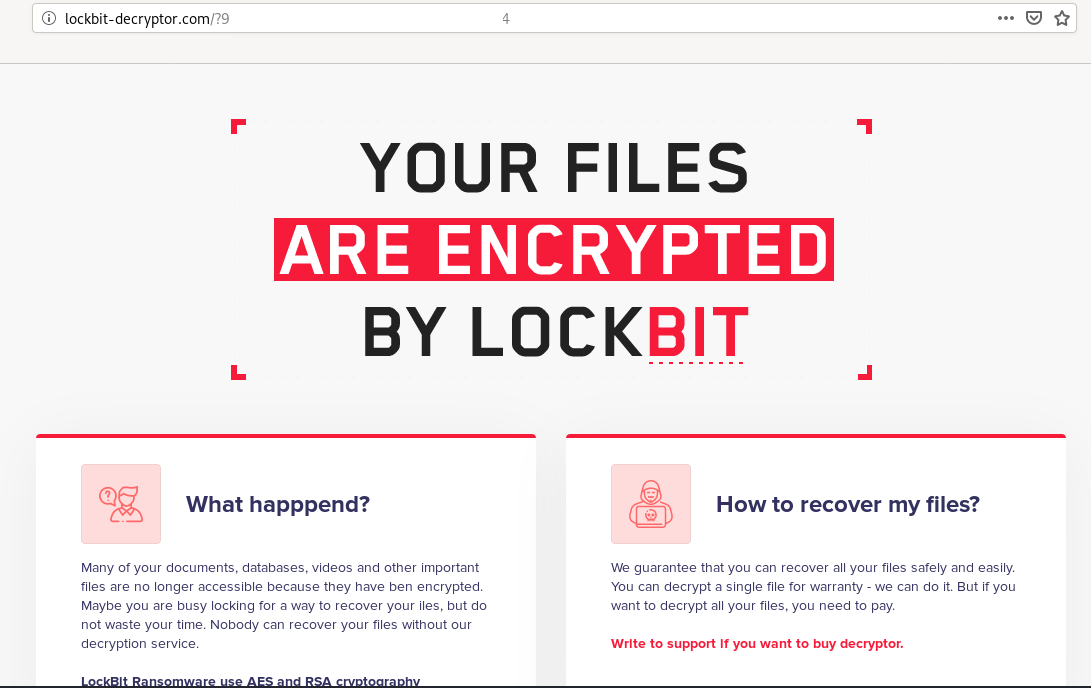

Ransomware attacks such as this one have been around since the early 2000s, in one form or another. But LockBit has an unorthodox business model: it’s arguably more of an illicit research lab than an organised crime syndicate. It consists of a core research team, who find vulnerabilities in corporate computer systems and develop an all-in-one hacking panel — complete with instructions — which is available to anybody who wants to try their luck the ransomware business.

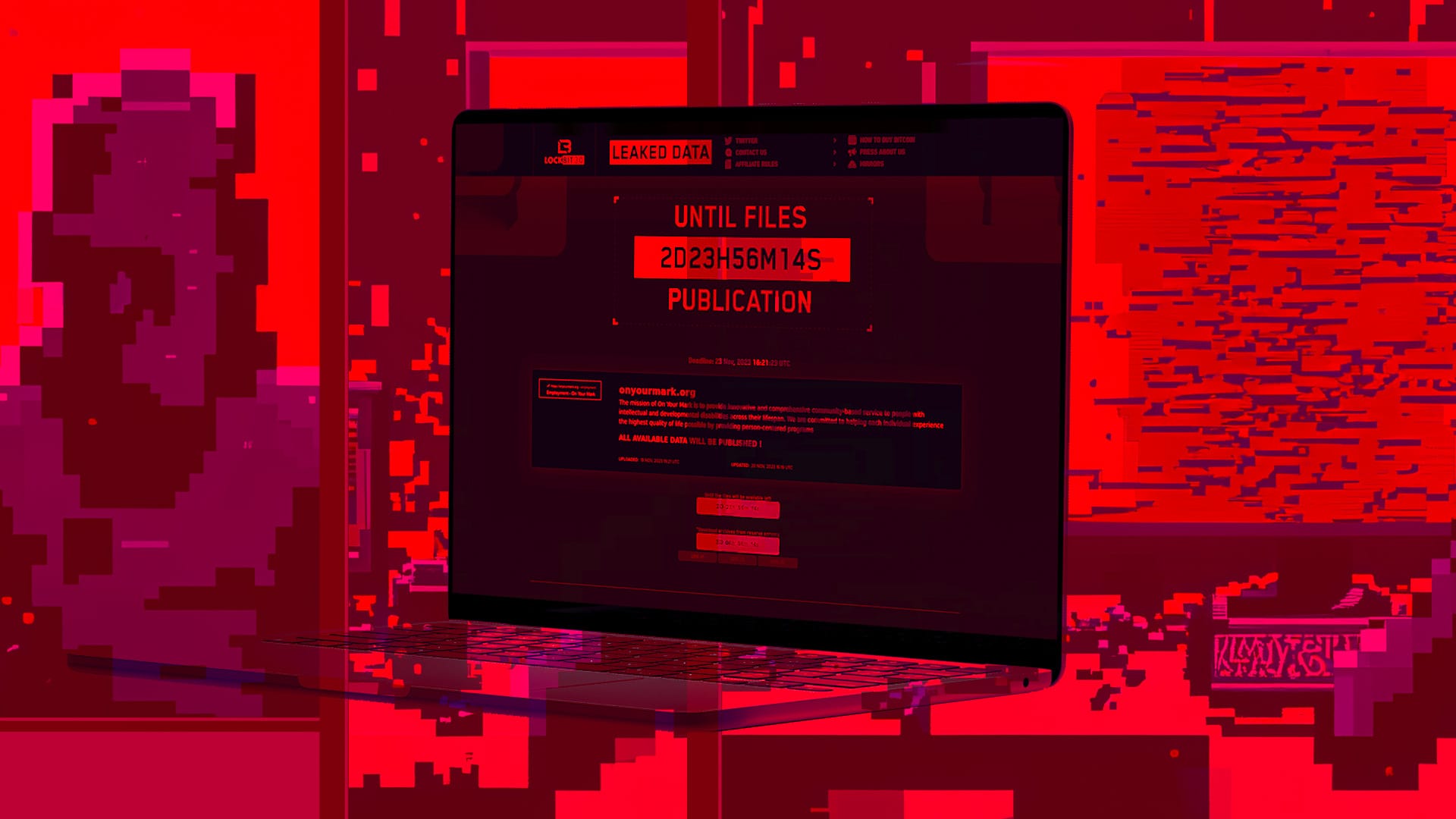

These customers (LockBit calls them “affiliates”) use LockBit’s system to enter a company’s systems and encrypt all of their files and replace their desktops with a ransom note: Pay up in 24 hours or risk having all of your documents published for anyone to see. If a ransom is paid to the affiliate, LockBit takes a commission – billing them for a portion of the "winnings."

Because of how easy it is to sign up for its affiliate system, LockBit has grown to become the largest single perpetrator of ransomware attacks on the internet. Their list of past targets is incredibly varied, too. There’s ICBC and Boeing, but also Gold’s Gym Saudi Arabia, a car dealership in Brisbane, and a nonprofit serving people with disabilities on Staten Island.

LockBit’s also very concerned about their brand image. They publish corporate-style job postings whenever they need to recruit, and have a penchant for publicity stunts — they once organised an academic essay-writing contest, offering prize money to their favourite ransomware research papers. And when an affiliate targeted a Canadian children’s hospital last year, LockBit published an apology and helped the hospital remove the malware. Hackers with heart!

Sometime in 2020, cybersecurity analyst Jon DiMaggio applied for a job posted by LockBit, posing as a German hacker. He didn’t pass the interview, but he was admitted to the group’s dark web group chat. Over the next year, he produced an exhaustive account of how the LockBit gang works. Here’s an excerpt from his series, Ransomware Diaries, that best illustrates one of the group’s other eccentricities:

In early September 2022, a member of the Russian forum LockBit frequents began a thread asking for suggestions for a "thematic tattoo” and tagged LockBit in the post. LockBit replied, offering to pay anyone who tattooed the LockBit name and logo on their body. The tattooed individual simply needed to post proof of the tattoo to collect payment. No one would tattoo a ransomware gang’s name on themselves, would they? Apparently, there are lots of stupid people in the world who will do anything for money. The LockBit circus was in full effect.

Despite LockBit’s prolific work, law enforcement have had a tough time catching up with them. Only two people associated with the hacker group have ever been arrested, and both appear to have only been affiliates. Ruslan Astamirov, a Russian living in Arizona, was arrested by the FBI in June after signing up for an online gambling website using his real name and the same email address he had used to shuttle his LockBit profits from one crypto wallet to another. The other, Mikhail Vasiliev, had forgotten to lock his laptop when police busted into his home in Canada. When investigators opened it up, they found an open browser tab on a site named “LockBit LOGIN” hosted on the dark web.

The founder of the group, who goes by the moniker LockBitSupp online, is seemingly untouchable — in interviews, he claims to have bought himself “a new helicopter and a mansion for Christmas.”

Get in touch with us: whalehunting@projectbrazen.com

You can also follow Whale Hunting on Twitter and Project Brazen on Instagram.

Join our Discord server to chat about Whale Hunting scoops, get behind-the-scenes insight into projects like Fat Leonard and join the hunt for Jho Low – we'll post clues as they come to us.

Support investigative reporting at Whale Hunting and get access to exclusive content every week by signing up for our paid subscription.